From failed promise to unlimited utility: Proactive voice-AIs with humans-at-the-helm

Introductory Series • Post 6

This is the second of four posts explaining why our proposed innovations—Proactive Voice-AI Agents (PVAIs) and User-Controlled Services (UCS)—will have a profound, positive impact on the nascent market for e-care—benefiting hundreds of millions worldwide and finally enabling us to use AI + the internet for the greatest good. Here, we examine why voice tech hasn’t lived up to its promise—and how PVAIs with humans-at-the-helm will unlock unlimited utility for caregivers and care recipients alike.

The vision of talking with computers using voice and conversational AI has motivated entrepreneurs and developers for 50+ years. From the Eliza experiment in 1966 to voice assistants like Wildfire in 1996, Siri in 2007, Alexa in 2014, and now ChatGPT and its competitors, innovators have tried to let users interact with computers and mobile apps naturally, just by talking. At each launch of these next-gen VAIs, industry pundits declared that this time, voice tech would transform the virtual world.

The latest book promoting this view—based on the rise of LLMs and GenAI—is The Sound of the Future: The Coming Age of Voice Technology by Tobias Dengel.

Like his predecessors, Dengel predicts that ChatGPT Voice and the like will “liberate us from these clumsy tools (i.e., keyboards, mice, and touchscreens) and return us to the innate form of communication we’ve known for thousands of years.” His enthusiasm even leads him to suggest that VAI adoption will “redefine how users interact with technology, much like the internet in the ‘90s and the smartphone in the 2000s.”[i]

The bumpy history of the voice space, however, offers no evidence that LLM-based VAIs will rival the internet’s impact unless and until they provide more value or utility than touchscreen alternatives—and address their shortcomings.

Prioritizing utility for users over value to app owners

The long-anticipated benefit of voice-UIs has been that they can be easier and quicker to navigate than the touchscreen-UIs we use instead. Remarkably, however, despite Amazon’s massive investment in Echo speakers and Alexa since 2015—which led to $10B in losses in 2022 alone[ii]--today’s VAIs have yet to convince users to choose voice over touchscreens for many, if any, of the most popular apps.

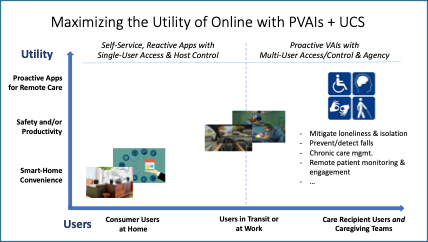

The matrix below shows how the lack of proactive VAIs + UCS has thus far limited the utility of VAIs to relatively simple apps or small populations of users.

The most common argument for VAIs on consumer devices—the convenience of not having to find, open and navigate an app using a touchscreen—is shown at the lower left.

At home, millions of us listen to music or set cooking timers using our voice instead of a touchscreen. We value VAIs even more when driving because it’s easier to get directions via voice and much safer. Similarly, physicians can’t pilot a mobile device when they operate, but they can speak to an “AI scribe” to enter data in an electronic health record (EHR).

All these voice-first apps, however, rely on the default, prompt-response, host-controlled services (HCS) model of today’s web. This means that the primary value users derive from them doesn’t change whether they’re accessed via touchscreen or voice—only the UI does.

Voice tech, in other words, has yet to provide more than hands- and eyes-free access to self-service apps designed to serve one user at a time via touchscreens.

Addressing voice tech and app market failures

On the other hand, the PVAIs suggested at the top right of the graphic—being configurable by caregivers and capable of speaking proactively to a care recipient—can and will provide unprecedented utility to both. Indeed, the fact that host-controlled apps can’t connect and serve both caregivers and their care recipients constitutes a costly failure of the market for mobile apps and online services.

When asked what specific, caregiving market failures might be addressed by PVAIs in the future, Claude.AI named three that strike us as both common and relatable:

“Information asymmetry” where caregivers are frustrated by incomplete, often-delayed information about their care recipient’s status or needs.

“Coordination costs” when care teams struggle to communicate with those they’re monitoring who don’t—often can’t—use touchscreens on mobile devices.

“Access inequality” when aging adults with dementia or other disabilities are excluded from digital content and apps that could benefit them most.[i]

A seismic step-up in utility and value

We believe that offering users control of proactive, voice-AI agents would quickly overcome these market barriers.

Caregivers would get more high-quality information about their loved ones on a daily basis as well as new tools to monitor and support them proactively. Care recipients would get intuitive, 24/7 voice access to well-informed, proactive care via a voice companion that can also help them access a variety of smart-home and online apps.

In short, these two paradigm shifts—PVAIs and UCS—will unleash a tidal wave of application innovation, adoption and added value that will truly be as transformative as the internet itself.

[i] “If voice-AI agents could be configured by family caregivers to speak to their care recipient in their homes, could they address any of these market failures and, if so, which ones?” and related prompts, Claude.AI, Anthropic, 23 September, 2025

[i] Tobias Dengel, The Sound of the Future: The Coming Age of Voice Technology (Public Affairs, 2023), p. 18-19.

[ii] Jake Swearingen, 2022, “Amazon thought Alexa would be the next iPhone. Turns out it’s a ‘glorified clock radio.’” https://www.businessinsider.com/amazon-alexa-business-failure-10-bn-losses-2022-11#:~:text=The%20Colossal%20Failure%20of%20Amazon’s,of%20gadgets:%20the%20smart%20speaker.

Business Insider